Inspiring Great Debates

This article was previously published on Quiet Revolution.

I remember well the first time I read Quiet Revolution. When I got to the page about the subarctic survival simulation used at the Harvard Business School, I was particularly intrigued. That’s because I used to be one of the professors who taught this case as part of the first-year MBA leadership course called LEAD. The simulation typically unfolded as Susan describes it. After their plane crashes in a barren, ice-capped wilderness, a surviving group of six to eight students must decide whether to stay put or attempt to hike to safety. They have to rank 15 items in importance according to their chances of survival. How will the team come to this decision?

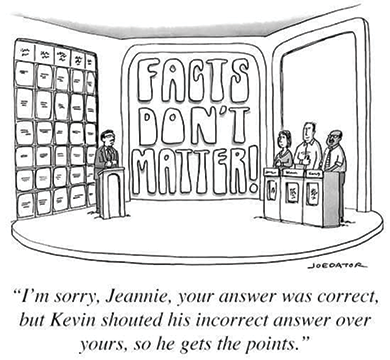

Well, as Susan writes and as I observed, the loudest, most extroverted students usually dominated. That made little sense, as it was rare that these students had relevant expertise. I sometimes heard students take control by saying, “Well, I hiked once in Yosemite, so I have some knowledge here.” Then these students blathered on about what to bring, picking—yes—the bottle of booze “to keep warm.” And so they would die (in this exercise).

It’s a great exercise because it reveals how many teams often debate. Some people—usually the extroverted loud mouths—dominate, even when they have the wrong answer (bringing the booze) and prevent others with more sage input from being heard.

This raises two fundamental questions: how can the quieter among us speak up? And how can managers run meetings so that everyone gets a chance to contribute, so that teams can make the best decisions? In my recent study—which I have published in my new book Great at Work—we investigated how key work practices of 5,000 managers and employees led to better performance. The best performers—including many introverts—found ways to speak up in meetings and to lead team debates that included everyone’s contributions.

As I discovered in my research, it’s not only introverts who struggle to speak up in meetings. It’s also true for ambiverts, and for people who feel intimidated in certain situations. I am an ambivert and there have been many times I have felt intimidated by a certain team situation and have not had the courage to speak up. Early in my career, when I joined the Boston Consulting Group, I attended an initial training session in a room filled with other recruits from places like Harvard and Stanford. That was intimidating for sure. We had to participate in one of those “thought experiments” in real time, estimating the number of cars on the road in the United States. One guy raised his hand and shouted out a range estimate, explaining the reasoning. The partner running the session exclaimed how well this new hire had answered the question. I thought the reasoning was totally flawed and wanted to say so in front of all these people, but I lacked the courage to raise my hand, so I remained silent.

I venture that this self-censoring has happened to most people at some point. Here’s an infamous example. When President Kennedy’s administration considered whether to launch an invasion to topple Fidel Castro in Cuba, several advisors thought the plan foolish but didn’t dare speak up. Among them was special advisor Arthur Schlesinger, who recounted a crucial meeting: “an intimidating group sat around the table—the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, three Joint Chiefs resplendent in uniforms and decorations.” Even though he opposed the plan, he couldn’t muster the courage to say so: “I shrank into a chair in the far corner and listened in silence.” The attempted invasion remains infamous to this day as the Bay of Pigs fiasco.

So how can we better speak up, even in meetings that are intimidating and where some extroverted loudmouths tend to dominate?

I’ve learned to prep for meetings by jotting down three insightful questions. At an appropriate time, I launch into one. I’ve found that posing a question is easier than making a full-blown argument.

Another tip is to build on someone else’s argument: “John mentioned increasing the price. I think that’s a good idea, and perhaps we should consider a 5 percent increase.” When you build on someone’s argument, you instantly insert yourself into the dialogue. You’re no longer lingering on the periphery of the group.

Another tactic is to make your views known to the team leader before the meeting. Hopefully, the leader will call on you at the appropriate time. That might put you in an uncomfortable position, but now you’re prepared to say something valuable.

Of course, it’s better if the manager in charge of the meeting creates a better environment so everyone feels able to speak up and contribute. In our study, the 36-year-old Dutchman Dolf Van den Brink did just that upon taking over Heineken’s sagging U.S. operations in White Plains, New York. When I interviewed him for my new book, he recalled that when he started, there was “a lot of fear” at the headquarters, and “nobody was speaking their mind.” Van den Brink hit upon the idea of using props to establish new expectations for meetings. When his team members filed into the room one morning, they noticed several 2×3 inch cards on the table. The red card read: Challenge, Have Another Solution. Another, a green card, declared: All In—Ask me Why! The last card was grey with a warning: Shiny Objects Alert, Get Back on Track. Every team member could grab and hold one of the cards to disagree (red), support a point of view (green), or refocus a colleague who was going off in the wrong direction (grey).

The Heineken Cards

Was this tactic silly? You bet! But on purpose. As Van den Brink explained, “What the presence of [the red card] meant was that anybody could legitimately raise a challenge.” By setting expectations and inviting people to speak, Van den Brink cultivated what Harvard professor Amy Edmondson calls an atmosphere of psychological safety. Van den Brink’s tactic worked. Over time, people on his team started to speak up. Soon the cards were no longer needed, and they disappeared from the room. Alejandra de Obeso, Chief of Staff at the time, noticed how the new expectations had enabled quiet people to participate vibrantly in the discussions. “There was one person with an introverted nature who significantly changed,” she remarked. “This person always had a very nuanced point of view of what was going on in meetings but was anxious about sharing it.” Over time, helped by a sense of inclusiveness and clear rules for allowing people to speak up, this person began to contribute, becoming “a reconciling force and taking the conversation a level further.” Van den Brink is confident that better discussions in the team played a major role in improving the innovation rate in the business and turning it around: “The more you can improve the quality of the debate, the better the quality of the outcomes.”

As my research demonstrates, we need better debates in meetings. And that means that everyone in the room needs to be able to contribute. Each one of us can take steps to speak up. And all managers can do a better job of including all viewpoints in the debate to help the team make better decisions and improve results.

This is not just about inclusiveness. It’s about improving performance.

Why do some people perform better at work than others?

Morten Hansen reveals the answer in his “Seven Work Smarter Practices” that can be applied by anyone looking to maximize their time and performance.